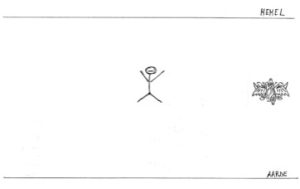

Man is an animal. But not just any animal. “Man does not live by bread alone.” He is a desiring creature. He is never content with the earthly here and now, but needs a heaven as well — a not-here and not-now toward which he can stretch, upright, as toward something that calls him beyond himself.

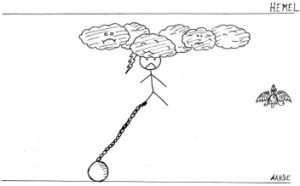

This in-between condition of the human being consists of two movements: an upward movement and a downward one. Normally these two movements are intertwined — like the two birds in the drawing — so that they keep each other more or less in balance. But sometimes one of these movements gains the upper hand, creating respectively an upward or a downward dynamic.

The Upward Dynamic

In his book The Paradise Bird, the Belgian author Louis Paul Boon uncovers the mechanics of the upward dynamic. When, in a mythical past, the city of Taboe is struck by famine, its desperate inhabitants see no other escape than, under cover of night, abandoning their emaciated children in the nearby mountains. In order to make this cowardly yet necessary practice somewhat more bearable, one of the townspeople, Noéma’s father, comes up with the idea of wrapping these secret killings in a consoling ritual: from now on the sacrificial children will be chosen by lot, and after a neat ceremony they will be allowed to leave the city through a beautifully decorated gate, a symbolic knapsack tied to their frail shoulders. The gate, formed by two panels shaped like angel wings and adorned with jewels, soon becomes an altar, and behind it Noéma’s father — compelled by circumstance — takes on the airs of a priest. He solemnly tells the parents and children of a Paradise Bird, “the golden bird who will descend upon you once your supplications reach his ear.” The sacrifices they now make will one day be rewarded.

One day, the lot falls on one of the priest’s own children. Noéma is an exceptionally intelligent, precocious girl. At first she walks, like all the others, unsuspectingly toward her snow-white death, but gradually she begins to see through her father’s well-intentioned lies. Little by little it dawns on her that she will not encounter the Paradise Bird on her trek through the mountains. This realization suffocates her, for she has absorbed the stories of the Paradise Bird eagerly since childhood; her very existence has become so inflated with the belief in that mythical creature that she cannot renounce it. It feels as though giving up the belief would mean giving up herself. And yet she cannot ignore her razor-sharp mind, which keeps confronting her with the insight that the Paradise Bird is nothing but fiction.

Her way out of this impasse is at once childlike and naïve, and yet also relentless and obstinate: if the Paradise Bird cannot come to her, she reasons, then she will go to the Paradise Bird. To one of the other children she says: the Paradise Bird “exists only within me, because I have kept believing in him, and therefore I must remain strong, keep showing myself strong, if he is to continue existing through me.”[i]

What Noéma effectively does is detach the belief in the Paradise Bird from the human context in which it arose — a context of lack and longing. She transforms the belief into a sacred, untouchable ideology, one that, so to speak, has always been there. If things are not yet ideal, she is effectively saying, this is not the fault of the ideology but of the human being, who is not yet ready for it. Humanity is still too bound to the earthly sphere of desire. Only after we have severed ourselves from that sphere will the ideology be able to fulfill its promises.

We find the same reasoning in every form of fundamentalism. The fundamentalist is not interested in the real human being — the one of flesh and blood, and therefore capricious and unreliable — but only in the higher human. The society the fundamentalist dreams of is a completely controllable, inorganic society — perfectly transparent, smoothly oiled, and egalitarian in the sense that everyone is interchangeable, everyone identical to everyone else. The fundamentalist dreams of a society that, instead of being composed of unique individuals, consists of cold, predictable robots.

That all fundamentalisms resemble one another so strongly is, in a sense, paradoxical. Every fundamentalist or radical movement prides itself on returning to its own roots (radix, radices), and one would therefore expect the many fundamentalisms to differ greatly, given their diverse origins. But the truth is that none of these movements is actually searching for its real roots. For just like Noéma, the fundamentalist knows all too well that such a search would yield nothing but an elusive and feral yearning — the kind that reigned in the city of Taboe at the time of the famine.

Instead of seeking the real roots — a search that becomes taboo — the fundamentalist prefers to swoon over a supposedly “pure” past to which all humanity must return. The mythologizing of the past is a frantic attempt to cover up the real past. It is an expression of the fundamentalist’s desire to tear longing itself up by the roots, and to plant in its place the thin, icy stem of his own system — whose growth he imagines as geometric, predictable, and controllable. And thus the open sky of the original religion disappears behind a set of dark clouds.

Whoever denies the existence of something cannot arm himself against it. Whoever denies the earthly within himself falls prey to it all the more easily. In The Paradise Bird, after a hellish trek through the mountains, the exiled children settle in a rocky gorge. Their clothes have long since worn out; they walk around naked. Noéma, however, is ashamed of the “marks of an animal origin” on her body and is the first to begin adorning herself again.

She denied that origin; she closed her eyes to the hairy triangle on her belly, the one pointing down toward the earth. And as if she could deceive herself, she girded her loins with a cloth of woven goats’ hair, upon which she had drawn another triangle: one pointing upward.

But it is precisely this concealment that fills the boys with something they had not known before:

“None of the young men could look at it without his member rising in a strange and hitherto unknown desire for that triangle.”[ii]

And even Noéma herself, without realizing it, falls under the spell of her own body. Her brother, the poet Tubal-Cain, remarks wearily:

‘I never fully understood it. I suppose that unconsciously, while her mind dwelled in a dimmer world, she had to maintain some contact with her own body. Her fingers proceeded like groping blind men. […] I could not restrain my eyes: I looked at Noéma, who had once again been exploring the land of her accursed sex, whispering of the indeterminacy of her soul (and what did she mean by this soul?), and my desire had been kindled. Behind the divine symbol on her belly I had seen the true sign of the animal.’[iii]

The fundamentalist is doomed to become ever more radical. His desire to eradicate desire remains… a desire. To drown out this troublesome humming insight within himself, he feels compelled to make the world crackle with explosions. The tragic horror of many terrorist bombings is that they do not serve to convince the world, but only to convince the fundamentalist himself. The detonations must prove how free he is from every trace of earthly doubt.

But in fact the only thing they prove is that the fundamentalist needs the world’s belief in order to believe himself, and that his doubt will vanish only once the whole world has been scorched by his fire. After each attack he will again discover doubt at the bottom of his soul. And time and again he will draw the same conclusion: that something must be wrong, not with the ideals he is pursuing, but with humanity itself. Not the ideology, but the human being must be remade.

Boon describes in his book how Noéma’s addiction to the Paradise Bird transforms her into a rational, fanatical ideology-machine. He writes:

‘She was a monster of religiosity, and all humanity was foreign to her. In order to secure the people’s happiness (for that was what she desired) she would have made each of them unhappy. In her struggle to prevail she had already destroyed every human sentiment in herself. She no longer knew personal happiness. She now appeared capable of committing murders, of offering people up on the altar where the winged beings kept watch.’

The Downward Dynamic

A philosopher who fiercely attacked the life-denying Noémas of this world was Friedrich Nietzsche. But Nietzsche went further: his goal was not only to excise the cancer of fundamentalism; in the same movement he sought to remove the maternal heaven in which the “decadent,” “mummifying” growths loved to nest. Put differently: Nietzsche refused to distinguish between the fundamentalist thunderclouds and heaven itself. For him, every longing for the higher was pathological.

Nietzsche prescribes his readers a peculiar cure: with muscular arguments he makes them lift weights of the most dizzying and disconcerting insights. Like a spry and cheerful athlete, he continually challenges them with the question of whether so many kilos of truth are still bearable — and whether perhaps another kilo might be added. It is clear that Nietzsche’s cure is not intended to produce weaklings. The ideal he envisioned was that of a human being without illusions — someone who would no longer need a heaven, who would coincide completely with himself in the here and now, and who would therefore no longer need to make of himself a project for the future. A person who would manage to shoulder the thought of the eternal return, and who would not hesitate to say “yes” when asked whether he would want every second of his life — “even this spider, even this moonlight between the trees, even this moment” — to be repeated exactly so throughout eternity. But the question is whether such a thing is still human: a person with no need of hope or horizons — is that still a person? Is that not rather the Übermensch?

In The Paradise Bird we encounter a certain Irad. It is not difficult to see in Irad a sort of Nietzsche. Living like a Dionysus among goats and rams, he delivers with mocking joy one “refreshing” truth after another. Not coincidentally, he is also Noéma’s arch-enemy. Of this Irad, the poet Tubal-Cain observes:

“Irad’s words made me nervous. They drove me to ask myself questions as well about the place of the human in this universe. Foolish, useless questions — inhuman questions even.”[iv]

It seems very much as though we, modern Westerners, have listened attentively to Nietzsche: not only have the fundamentalisms lost their charm for most of us, we also succeed rather well in disarming all our “higher aspirations” with a proper dose of irony. Chanting slogans like “God is dead!” and “The Grand Narratives are no more!”, we like to believe that we have finally outgrown our wild youth of the past twenty-five centuries. But does that make us Übermenschen? Can we really do without a heaven?

We gladly deny our aspiration toward the higher. But does not the same apply here as it did for the fundamentalist — namely, that what one denies presses itself upon one all the more forcefully? By denying the pull toward the higher, we make it easier for countless marketers to exploit it: we believe in nothing anymore, yet we buy the umpteenth gadget that promises us paradisiacal happiness, or yet another product with which we will supposedly be able to “be ourselves.” Precisely because we refuse to look at the heaven, we cannot see that a great cinematic screen has been stretched across it, onto which all manner of fabricated needs and desires are projected — a false heavenly glow. Rather than becoming ever more unique adults with ever more finely tailored desires — let alone Übermenschen with individualized value-systems — we increasingly resemble interchangeable infants, all crying the same thing: more! It is ironic, but such a society unmistakably resembles the one the fundamentalist dreams of — only he would project a different film on the screen.

We could, of course, look for remedies. But perhaps the very belief in remedies is one of the symptoms of our condition — our ingrained scepticism on the one hand, and on the other our greedy willingness to believe in miracle cures.

Perhaps, then, we should simply acknowledge our longing for the higher, so that we might find a way of dealing with it healthily: not by narrowing our entire lives to it (fundamentalism), nor by denying it altogether (consumerism), but by seeking a golden mean. Perhaps then we may finally be able to see the heaven as it truly is: a heaven open enough to make room for our desires, yet open enough also to let a life-affirming current descend toward the earth — as is always the case with good art and with religion in its best sense.

Notes:

[i] Boon, Louis Paul, De paradijsvogel, Amsterdam, Antwerpen, De Arbeiderspers, 1999 (eerste druk 1958), p. 36

[ii] Boon, Louis Paul, De paradijsvogel, Amsterdam, Antwerpen, De Arbeiderspers, 1999 (eerste druk 1958), p.69

[iii] Boon, Louis Paul, De paradijsvogel, Amsterdam, Antwerpen, De Arbeiderspers, 1999 (eerste druk 1958), p. 64

[iv] Boon, Louis Paul, De paradijsvogel, Amsterdam, Antwerpen, De Arbeiderspers, 1999 (eerste druk 1958), p. 87